Research

Our research in fungal systematics is concerned with fungi that cause disease, elicit allergic or hypersensitivity responses, produce toxins or metabolites of medicinal or industrial importance, and occupy vertebrate-associated habitats where they decompose keratinous substrates. Our studies of morphology and life histories of fungi are important to an understanding of the biology, diversity and distribution of medically important fungi and their impact on human and animal health. Support for our research has come from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, the University of Alberta Small Faculties Fund Support for the Advancement Scholarship and other agencies. See publications.

A practical goal of our work is the improved ability to diagnose fungal disease especially infections caused by unusual or novel pathogens. Our identification of the causative agent often leads to case reports in which taxonomy of the fungus is an important component.

Fungi causing contagious disease in reptiles.

Fungal growth from a skin biopsy of a snake.

Over the three decades, severe and often fatal skin disease has been increasingly recognized in captive and wild reptiles including lizards, snakes, crocodiles and tuataras. The fungi involved have been identified in prior publications under the names Chrysosporium anamorph of Nannizziopsis vriesii (CANV-complex), Chrysosporium guarroi, Chrysosporium ophiodiicola and Chrysosporium species, but the relationship of these fungi to each other and to fungi within the ascomycete order Onygenales was unresolved.

In 2013, two molecular analyses of fungal isolates grouped under these appellations led to major taxonomic revisions and revealed new insights into the biology of these reptile pathogens (Sigler et al 2013; Stchigel et al Persoonia 31:86-100 2013). All CANV-complex isolates were found to differ from Nannizziopsis vriesii and were assigned to 16 species, either within Nannizziopsis or within the new genera Paranannizziopsis and Ophidiomyces, and 14 of these species were newly described. Our study demonstrated that the reptile pathogens and some human isolates belonged in three well-supported lineages, representing the genus Nannizziopsis and two new genera Ophidiomyces and Paranannizziopsis within the Onygenales. An review of the reptile fungal pathogens and the infections they cause is in press (Pare & Sigler, J Herp Med Surg; accepted 22 Oct 2015).

The genus Nannizziopsis includes species associated with infections in chameleons, geckos, crocodiles, agamid and iguanid lizards as well as humans. Severe contagious disease is common among green iguanas (Iguana iguana) and pet inland bearded dragons (Pogona vitticeps) and has been termed the Yellow Fungus Disease (see link). Nannizziopsis guarroi is now known as the agent of such infections described formerly under the names Chrysosporium guarroi or as CANV. In contrast, infection in coastal bearded dragons (Pogona barbata) from Australia is caused by a separate species, Nannizziopsis barbata.

Outbreaks of cutaneous and often fatal infection in chameleons and leopard geckos similarly have been attributed originally to CANV. Infections in chameleons are now known to be caused by the new species Nannizziopsis dermatitidis. The fungus involved in the leopard gecko outbreak, involving 80 animals, is not precisely determined but molecular analysis indicates a relationship with Nannizziopsis arthrosporioides based on high ITS sequence similarity (577/579 bp). An outbreak of fatal skin disease documented in farmed Australian saltwater crocodiles was caused by Nannizziopsis crocodili.

Images (left) show colonial and microscopic appearance of Nannizziopsis guarroi, a leopard gecko infected with Nannizziopsis dermatitidis (courtesy ER Jacobson) and (right) Nannizziopsis crocodili shown by scanning electron microscopy.

lesions on snake Holocephalus bungaroides (D. McLelland)

Isolates from terrestrial snakes belong exclusively to the new genus Ophidiomyces and to the single species Ophidiomyces ophiodiicola (formerly Chrysosporium ophiodiicola), whereas isolates from aquatic and semi-aquatic snakes and from tuataras are placed in the genus Paranannizziopsis.

Ophidiomyces ophiodiicola is the cause of Snake Fungal Disease [SFD] (see link), a contagious disease affecting populations of free-ranging and captive snakes and now recognized as an emergent global threat to populations of endangered wild snakes (Pare & Sigler, J Herp Med Surg; accepted 22 Oct 2015). Infections in snakes progress rapidly and are often associated with conspicuous lesions of the head and ventral scales and with brown plaques, crusts or nodules as described in the first case report involving O. ophidiocola in captive brown tree snakes. The first case of SFD in Canada has been confirmed in an eastern fox snake by culture and ITS sequencing (L. Sigler 2015 unpubl data).

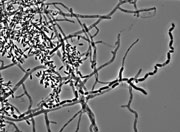

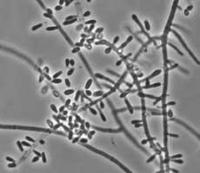

Ophidiomyces ophiodiicola UAMH 10768 colonial and microscopic features including aleurioconidia, fission arthroconidia and undulate hyphae.

Isolates from infected aquatic and semi-aquatic snakes belonged to the new genus Paranannizziopsis. Although infected tentacled snakes (Erpeton tentaculatum) housed in a zoo in Canada and in the USA presented with similar clinical findings, the causal fungi belonged to two different species, Paranannizziopsis crustacea and P. californiensis. A third species, P. australasiensis, infected captive tentacled snakes in Australia and tuatara in a New Zealand zoo.

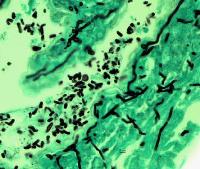

Images (left) show Paranannizziopsis crustacea in a skin biopsy and in culture.

Infections caused by Nannizziopsis, Paranannizziopsis and Ophidiomyces are contagious among reptiles but no species causing infections in reptiles has been found to cause disease in humans. No human-associated Nannizziopsis species has been found in reptiles, nor have these species been shown to be contagious.

Histopathology, PCR assays, and culture are important in confirming a diagnosis of fungal infection in reptiles. Almost all species produce cylindrical fission arthroconidia both in fungal culture and in cutaneous tissues, and these arthroconidia appear to be the primary propagules for transmission of infection between reptiles. In an experimental evaluation of pathogenicity, N. dermatitidis applied directly to intact or abraded skin induced skin lesions in 60% of healthy veiled chameleons and the fungus could be isolated from air and environmental materials of the caged animals. In another study, we showed that there is a low prevalence of the “CANV” on the shed skins of healthy captive reptiles but a high prevalence of saprophytic fungi. See book chapter by Pare et al for further information on fungi causing disease in reptiles.

Fatal infection in chameleons

A fungus causing an outbreak of systemic infection in a group of veiled chameleons (

Chamaeleo calyptratus) was described as a new genus

Chamaeleomyces granulomatis using morphological and molecular data. The affected chameleons were housed in a zoo collection in Denmark. The disease was notable for the development of large granulomas in multiple organs and the presence of large yellowish while nodules that were grossly visible in the liver and other organs.

Fungal isolates from the various tissues were initially suspected to represent Paecilomyces viridis, a species previously identified as the cause of a single outbreak of fatal mycosis in carpet chameleons. However, molecular data revealed that the Danish isolates represented a new but related species and that both species were members of a new genus within the ascomycete family Clavicipitaceae, that includes many insect pathogens. It is likely that the chameleons acquired the infection by ingesting infected insects. Many entomopathogenic fungi infect insects by penetration through the cuticle, followed by growth within the hemolymph in the form of yeast-like cells. Similarly, members of the genus Chamaeleomyces grow in the infected tissues of chameleons in the form of yeast-like cells and fungal filaments.

Images show lesion on veiled chameleon (courtesy M. Bertelsen) and colonial and microscopic appearance of Chamaeleomyces granulomatis.

Fungi isolated from shed skins of captive reptiles

Chlamydosauromyces punctatus, a new ascomycete and Acremonium exuviarum, a hyphomycete, were isolated from skin of a frilled lizard (Chlamydosaurus kingii) and Solomon Island skink (Corucia zebrata), respectively. Only a single isolate of each species is known and neither is associated with pathogenicity.